The U.S. invented nuclear power— yet today, it’s the nation with the largest volume of nuclear waste and the least progress toward a real solution.

Meanwhile, a Nuclear Renaissance is gaining momentum—socially, politically, and commercially-while the back-end of the fuel cycle remains largely ignored.

Our first argument: this is a problem with real consequences.

The waste issue is a rapidly growing safety and infrastructure liability, a looming bottleneck for SMR commercialization, and a compounding taxpayer burden with no long-term owner.

Second, we believe regulators will eventually align with the scientific consensus: deep geological repositories are the way forward.

Over time, we also expect a reversal of the decades-long U.S. moratorium on reprocessing—unlocking the two most credible long-term strategies for closing the back-end of the fuel cycle.

Ultimately, we see this messy, underbuilt, and often-avoided domain—perhaps the most complex problem in the entire nuclear stack—as a defining opportunity. Whoever helps solve it will be in pole position to own the architecture of the next nuclear era.

Why Do We Care About Nuclear Power At All?

Nuclear is energy abundance, and energy abundance is what powers progress.

We live in a thermoeconomic civilization, where economic growth, technological advancement, and global stability are fundamentally constrained or enabled by energy availability. (see next slide)

As our ambitions grow, so does the energy it takes to realize them:

AI is a textbook example: training frontier models demands exponentially more power, from GPUs to data centers to cooling systems.

Sending a man to the moon required more energy than building an aircraft carrier — which itself required more than powering the steam-driven factories of the first industrial age.

Today’s goals — AI, space, synthetic biology, re-shoring — will demand more still.

And it just so happens that nuclear remains the highest energy-density power source available to humanity. Doubling down on nuclear is humanity’s clearest path to climbing the Kardashev Scale.

The relationship between economic growth and energy abundance is not just correlative. Energy abundance is a prerequisite to economic abundance.

Energy use per person vs. GDP per capita, 2023

Nuclear is strategic power. It’s not just about energy. It is about sovereignty, resilience, and geopolitical leverage in a world where power dynamics are hardening.

China has grown its nuclear output 25x since the early 2000s and is surging ahead with 29 reactors under construction.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has none.

Nuclear is clean baseload power. Renewables are great—we need a ton of them. But they’re intermittent. If we want 24/7 carbon-free electricity, nuclear is the only mature option.

Electricity generation for China, Europe, India, and the U.S.

Data source: Ember (2025); Energy Institute – Statistical Review of World Energy (2024), via Our World in Data.

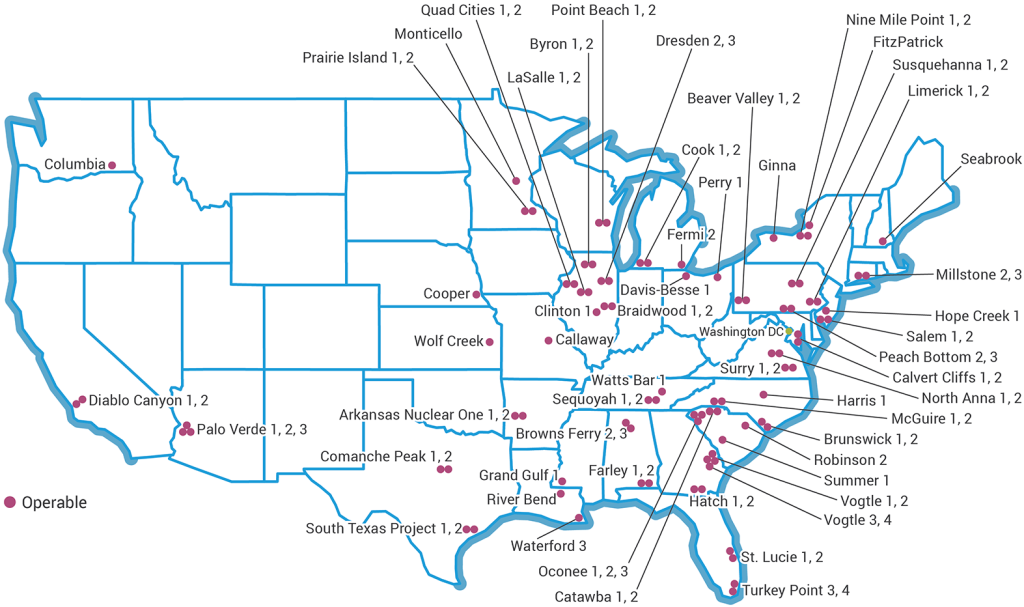

This Is What Our Current Reactor Fleet Looks Like

- 94 reactors across 54 plants

- Total capacity: ~96 GW

- Supplies ~18% of U.S. electricity

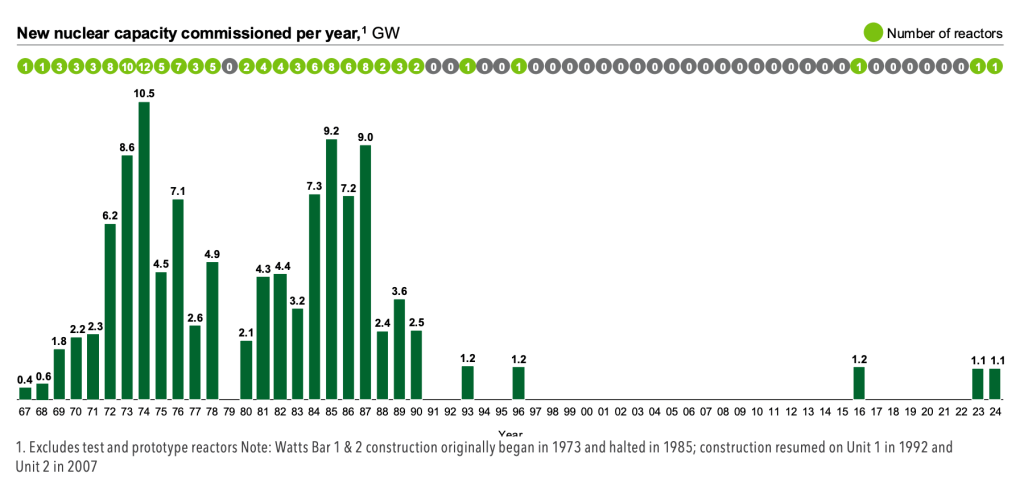

Most of This Fleet Was Built in the 1970-80s

But Political Momentum Is Finally Happening

Bipartisan momentum in Congress: Both Republicans and Democrats now consistently support nuclear energy, with multiple pro-nuclear bills passing with bipartisan majorities (e.g., ADVANCE Act, Fission for the Future Act).

Executive-level support: In June 2025, President Donald Trump signed a series of Executive Orders signaling that “the time is ripe for an American nuclear renaissance.”

Federal funding tailwinds: The IRA, Infrastructure Law, and DOE Loan Program have unlocked billions in tax credits, R&D, and capital support for advanced nuclear.

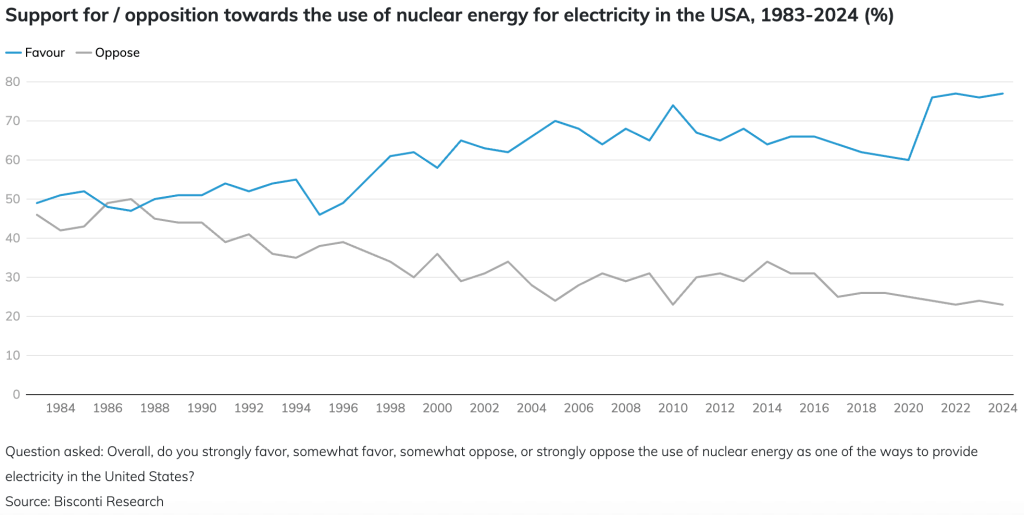

And Public Perception Is Rallying Too

Decades after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 triggered a sharp drop in public trust, sentiment is finally shifting.

Today, a majority of Americans support more nuclear power.

Capital Is Mobilizing — This is Where It is Flowing

Investors are waking up to the urgency of scaling the nuclear fleet, and capital is finally flowing in to support the development of next-gen reactors.

| Microreactors | Valar Atomics, Oklo (Altman) |

| SMRs | TerraPower (Gates), NuScale Power, X-energy, Terrestrial Energy, Kairos Power, Newcleo (using reprocessing, based in France) |

| Fusion | Fuse Energy, Helion (Altman, LSVP, SoftBank), Commonwealth Fusion, Pacific Fusion (Gates, GC, LSVP, Elad Gil, etc) |

| Project Development | The Nuclear Company, Elementl Power, Alva, Oppenheimer Energy |

Capital Is Mobilizing — This is Where It is NOT Flowing

Despite investments in next-gen reactors, minimal capital has been flowing towards the front-end of the nuclear fuel cycle — while the back-end is still largely ignored.

| Fuel Cycle Front-End | Uranium & Fuel Procurement | General Matter (Founders Fund), Standard Nuclear |

| Next-Gen Reactors & Development | Microreactors | Valar Atomics, Oklo (Altman) |

| Next-Gen Reactors & Development | SMRs | TerraPower (Gates), NuScale Power, X-energy, Terrestrial Energy, Kairos Power, Newcleo (using reprocessing, based in France) |

| Next-Gen Reactors & Development | Fusion | Fuse Energy, Helion (Altman, LSVP, SoftBank), Commonwealth Fusion, Pacific Fusion (Gates, GC, LSVP, Elad Gil, etc) |

| Next-Gen Reactors & Development | Project Development | Fuse Energy, Helion (Altman, LSVP, SoftBank), Commonwealth Fusion, Pacific Fusion (Gates, GC, LSVP, Elad Gil, etc) |

| Fuel Cycle Back-End | Nuclear Waste Disposal | Kurion (Lux, acq. by Veolia) |

We’re Building A Nuclear Future With No Plan for the Back-End

A Nuclear Renaissance is happening, but no one’s asking the question of whether we have a back-end plan to deal with all the waste.

Turns out, we don’t — not even the beginning of one.

The near-total neglect of the back-end is striking us as a glaring misallocation of political and financial attention.

It matters-for investors, developers, and policymakers—because so much of the future we’re betting on implicitly assumes the waste problem will get solved.

Quick Primer on Nuclear Waste

The nuclear fuel cycle generates two broad waste streams:

- Front-End Waste: Produced during mining, milling, enrichment, and fuel fabrication. Includes uranium tailings, chemical residues, and low-level radioactive materials. Typically stored near production sites in lined ponds or capped impoundments.

- Back-End Waste: Generated after fuel is used in a reactor. Primarily composed of spent nuclear fuel (SNF) — highly radioactive, thermally hot material requiring shielding and cooling.

This article focuses on the back-end — where the waste is most hazardous, politically fraught, and logistically unresolved.

SNF is especially hazardous as it constitutes a major threat to human health for at least 10,000 years and remains radioactive for several million.

We’re Sitting on a Huge Backlog

As of early 2025, the United States inventory of commercial spent nuclear fuel (SNF) has reached approximately 89,000 metric tons of heavy metal (MTHM), alongside 90 million gallons of defense-related high-level waste (HLW).

These casks were designed for temporary use, but now serve as the default solution in the absence of a permanent repository.

That number grows by ~2,000 MTHM per year.

Among the 75+ sites across 30+ states storing spent nuclear fuel, over 20 are fully decommissioned reactor sites where the only remaining facility is an Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (ISFSI).

No country in the world generates more nuclear power with less of a long-term plan.

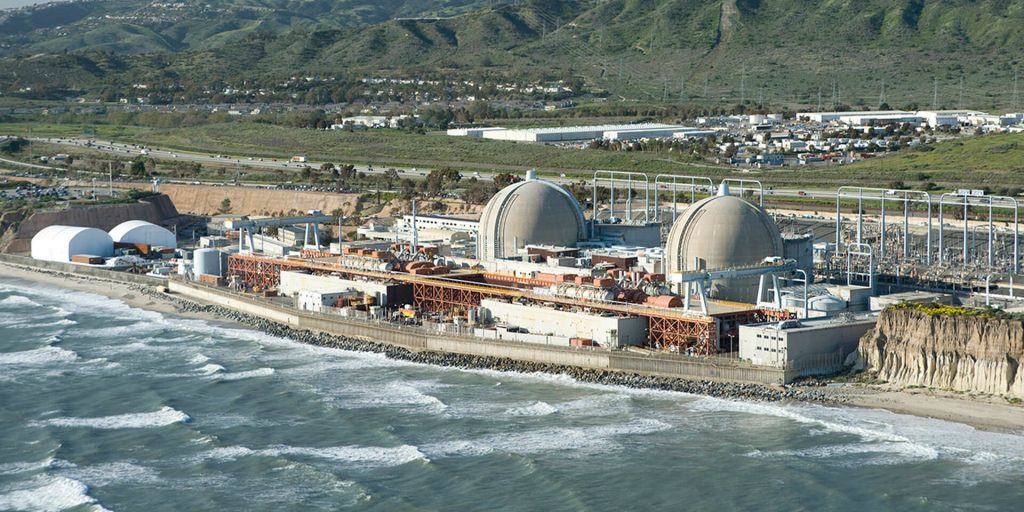

Here is an example of San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in California.

Shut down in 2013, but still maintained to store ~1,800 metric tons of stranded spent nuclear fuel.

San Onofre is one of ~23 fully decommissioned U.S. nuclear plants where only the dry cask storage facility (ISFSI) remains.

We’ve Normalized a Status Quo of Indefinite On-Site Storage

Dry cask storage: how nearly all spent nuclear fuel is stored in the U.S. today — above ground, on-site, indefinitely.

Over 3,000 dry casks are now deployed across 75+ sites in more than 30 states.

Dry Casks Are Safe Today, But Create a Growing Infrastructure and Security Liability

Dry casks are technically sound, but aging. Dry casks are designed to safely contain spent fuel for decades. Heavy metal shielding and radioactive decay products make theft nearly impossible without industrial-scale effort. But over time, that protective radiation barrier fades, making proliferation risks very real.

They were never built for the long haul. Casks are licensed in 20-year intervals, renewable up to 100 years. But beyond that, there are no guarantees. Corrosion, heat, and radiation slowly degrade materials – and sooner or later, repackaging or relocation will be required (per NRC).

The real problem is scale and sprawl. The U.S. has thousands of dry casks spread across 75+ sites, many of them at decommissioned reactors with no staff or permanent infrastructure.

N.B.: There’s no unified federal standard for site security. Each ISFSI follows NRC guidance, but enforcement is uneven — and some operate with minimal physical protection.

Why This Problem Is Going to Compound Exponentially

If we draw a trendline from where we currently stand, and look 20 years into the future — with dozens of new reactors expected to come online — the risks tied to dry cask storage don’t just persist, they compound:

Total waste volume will keep going up. We currently have a backlog of ~89,000 metric tons of spent fuel. Projections indicate that by mid-century, this number will be approximately ~136,000 metric tons.

The longer we wait, the harder and more expensive it gets to fix. As casks age, they require more care to handle safely — making it harder to inspect, move, or repackage them. Delaying action just drives up the cost and complexity of future remediation. (see next slide)

The problem doesn’t just deepen, it spreads. Plans to roughly double the U.S. reactor fleet will bring new reactors, and with them, new dry cask storage pads. In the absence of a long-term waste strategy, each new site becomes another stranded node in an expanding, decentralized, and aging waste network.

Delaying Action Has Massive Cost Implications For Taxpayers

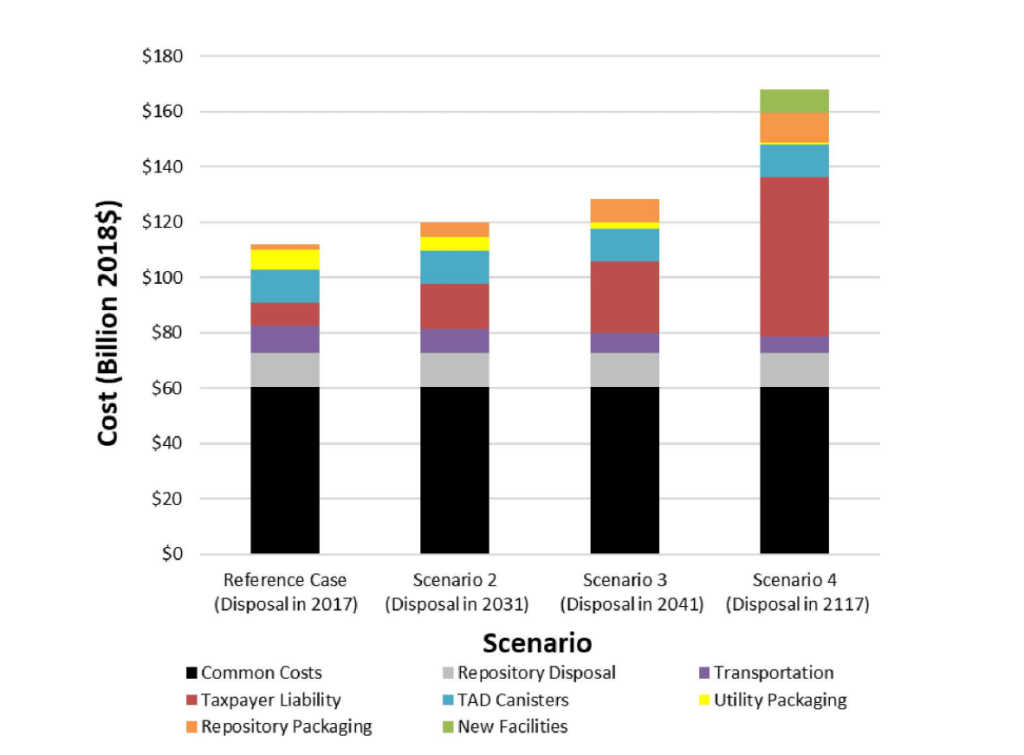

In 2018, Sandia National Laboratories (managed by DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration, and widely regarded as one of the most technically rigorous institutions in the U.S. nuclear ecosystem) conducted a comprehensive cost analysis of long-term nuclear waste strategies.

The study compared the total system cost of four scenarios, each defined by when permanent disposal of spent nuclear fuel begins, and used Yucca Mountain disposal starting in 2017 as the reference case (more on Yucca Mountain in next chapter).

The goal was to measure how delaying disposal drives up total lifecycle costs – including storage, repackaging, transportation, repository development, and taxpayer liability.

Sandia’s findings were unequivocal: delaying repository construction by 100 years is the most expensive path, costing taxpayers over $55 billion more than if disposal had begun in 2017.

N.B: these numbers only account for spent fuel discharged as of 2018. As the U.S. nuclear fleet grows, these numbers should be seen as a conservative floor.

Inaction is expected to drive a >$55B taxpayer liability

Comparison of Estimated Costs for Different Repository Opening Dates. Data source: Freeze, Geoffrey A., et al. Comparative Cost Analysis of Spent Nuclear Fuel Management Alternatives., Jun. 2019.

Delay Also Creates a Looming Threat for SMR Deployment

SMR demonstrations are expected around 2027-2028, with commercialization targeted for the early to mid-2030s. But a critical obstacle lies ahead: siting new reactors requires intensive community engagement, and today’s unresolved waste problem makes that process much harder.

SMR deployment demands deep engagement with local communities, often through dozens of public hearings and comment periods per project.

These hearings are not symbolic: federal public engagement is mandatory in all 50 states under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which governs NRC siting processes nationwide. The outcomes of these sessions can directly shape the timeline, scope, or viability of a project.

E.g., Seabrook remains one of the most illustrative examples of how public pushback can derail a nuclear project. Two units were planned, but only one was built due to public resistance.

Delay Also Creates a Looming Threat for SMR Deployment

Now, waste is now one of the top concerns raised during public hearings. Without a clear answer to where the spent fuel will ultimately go, reactor developers are likely to face licensing delays, and in some cases, full project cancellations – especially as siting processes become more community-driven. Just because investors aren’t pressing on waste today doesn’t mean communities and regulators won’t.

With so few nuclear projects going through commercialization in the past 30 years, institutional memory is thin. There’s little precedent to guide (or warn) the current wave of developers.

Crucially, most of the U.S. reactor fleet was licensed in the 1970s-1980s, that is, at a time when developers could still promise with a straight face that a federal waste solution was coming. As we shall see next, that is simply not the case anymore.

Tl;dr —What Is the Nuclear Waste Problem, and Why Is It Critical We Solve It?

As of 2025, nuclear waste is:

1. A compounding infrastructure and security liability, with thousands of dry casks stranded across the country and no permanent solution in sight.

2. A taxpayer liability, already costing over $9B in federal reimbursements – and poised to grow massively.

3. A looming commercialization threat. As developers prepare to deploy new reactors, they’ll need a credible plan for what happens to the waste after use. Right now, they can’t point to one.

Hence, solving the waste problem means three things: replacing today’s patchwork of stranded waste with the resilient, long-term infrastructure America deserves; stopping the money bleed; and unlocking the backbone needed to power the nuclear century.

Leave a Reply