Geothermal energy is increasingly recognized as one of the most underappreciated yet potentially transformative pillars of the clean energy transition.

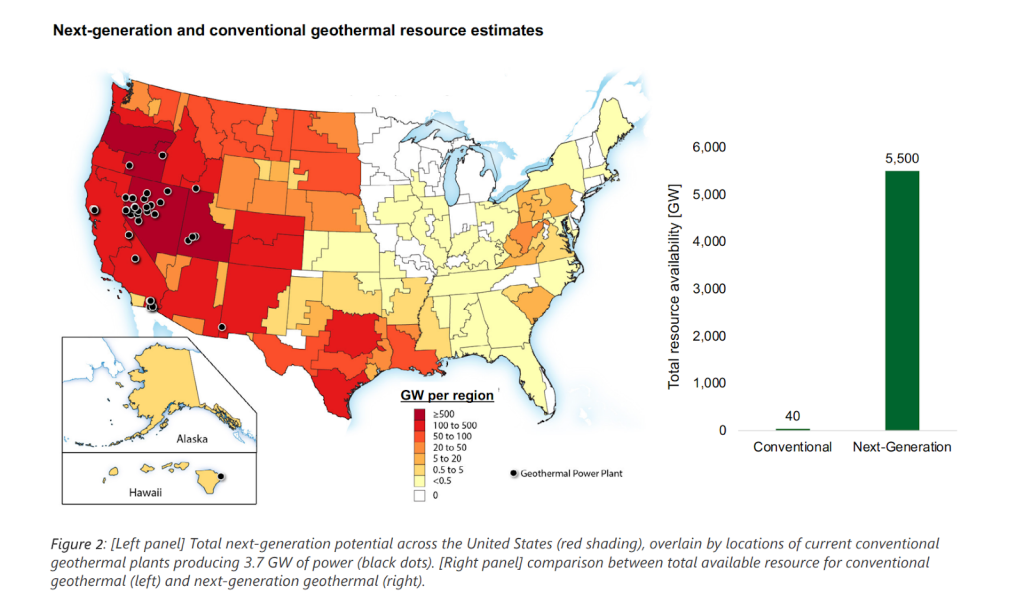

The United States has an estimated 5.5 terawatts of next-generation geothermal potential, enough to power the country for thousands of years.

The primary obstacle to development is not a lack of resources, but rather the technology and cost-effectiveness of extraction. This energy is available nationwide, including the eastern U.S., and is mainly being developed through two approaches: Enhanced Geothermal Systems and Closed Loop systems (source)

While today’s global market remains relatively small at roughly $7 to $10 billion with about 15 gigawatts installed, advances in Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), closed loop designs, and next generation drilling technologies have positioned the sector for substantial growth, with EGS systems already becoming the fastest growing category of geothermal technology in the U.S, with announced projects totalling 1,895 MW in nameplate capacity, and 451 MW in pre-construction.

Unlike solar and wind, geothermal provides always on, dispatchable baseload power with capacity factors of 75 to 90 percent, making it well suited to support electrification, grid reliability, and the rapidly increasing energy demand from data centers.

But then, how does it compare to Nuclear and Geothermal, which are both sources that are capable of delivering base load power? Let’s have a look.

Comparing Geothermal with Nuclear and Natural Gas

Geothermal offers reliable baseload power with strong long-term potential. Next-gen technologies like Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) could supply up to 15% of new global electricity by 2050.

Capital costs ($3,700–28,000/kW) are higher today, but dispatchability, low carbon footprint, and improving drilling economics make it a strong growth candidate to meet decarbonization goals.

Nuclear provides stable, zero-carbon baseload power, but economics remain challenging due to very high capital intensity and long construction timelines.

The emerging Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) market is promising but requires policy support and standardization before scaling.

Natural Gas is today’s low-cost, flexible benchmark, critical for grid balancing. However, exposure to volatile fuel prices and high carbon taxes ($50–100+/t CO₂) poses risks to competitiveness.

Market Outlook

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates the technical resource potential for next-gen geothermal in the U.S. alone exceeds 5,000 GW, which is more than four times the current capacity of the entire U.S. power grid and around 140 times as much as conventional geothermal. Globally, the TAM is multiples larger.

The DOE’s Liftoff Report projects next-gen geothermal could reach 90 GW of installed capacity in the U.S. by 2050, representing over $200 billion in cumulative capital deployment. This implies an exponential growth curve, with significant acceleration expected post-2030

The Different Types of Geothermal Technologies

Geothermal energy today splits into two approaches.

Conventional hydrothermal systems (dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle) tap natural underground reservoirs and account for the entire 15 GW of current global capacity.

Unconventional engineered systems could expand the accessible resource base by roughly 2,000 times.

These include EGS drilling 3 to 10 km deep, Advanced Closed-Loop systems (ACL) at 3 to 8 km depths, and Superhot Rock projects targeting extreme depths of 8 to 20 km.

Binary cycle technology serves as the bridge, generating power from lower temperatures and opening up roughly 100 times more viable sites than traditional plants.

Each approach has trade-offs. EGS offers scalability but carries seismicity risks.

ACL avoids seismic concerns but remains technically complex and expensive.

SHR promises 5 to 10 times more energy per well but sits decades away from commercial viability.

Conventional hydrothermal works commercially today, EGS and ACL are in pilot demonstrations, and SHR remains in the research phase.

Tailwinds and Barriers

Several structural tailwinds support geothermal’s expansion.

These include bipartisan policy backing, cost reductions enabled by technology transfer from the oil and gas sector, and broad applicability across power generation, heating, and industrial uses.

Direct use applications such as district heating and industrial process heat extend geothermal’s relevance beyond electricity. Alignment with existing oil and gas supply chains also helps reduce deployment and scaling challenges.

At the same time, notable barriers remain.

These include high upfront capital requirements, lengthy permitting timelines for drilling approvals under NEPA where as many as six separate reviews may be required and remain a key source of delay, and public perception challenges in certain markets such as Japan.

Despite these constraints, early projects from companies such as Fervo, Eavor, and Sage Geosystems have demonstrated technical feasibility. In parallel, the U.S. Department of Energy projects levelized costs of energy declining from roughly $100 per megawatt hour today to $45 to $65 per megawatt hour by 2035.

Taken together, these developments indicate that next generation geothermal, particularly Enhanced Geothermal Systems, is moving from a niche technology toward a scalable and system critical energy resource.

Continued technological progress, supportive policy frameworks, and the emergence of project finance for proven systems are improving cost structures and enabling wider deployment across power, heating, and industrial markets.

Leave a Reply